The DLATO core database was built in PostgreSQL. The DLATO projects that rely on the core database structure each run a clone of the core data base, which is then altered to facilitate the specific project's needs. As a relational database it is fully expandable to capture any type of data about a textual object.

The DLATO core database is based on James D. Moore's own research database, which was migrated to PostgreSQL and restructured in 2020 and has been adding features ever since. The core build was designed for efficiency of data input, automation of data organization, and expandability.

What is PostgreSQL and a Relational Database?

PostgreSQL (or simply Postgres) is the preferred open source relational database software for scientific projects. Relational databases create connections between various tables of data using a unique id for each discrete datum. When all tables in a database are related any datum in the database can be queries or used alongside any other datum. In practical terms for DLATO projects, this allows one to easily compare or order data using both linguistic and descriptive information at the same time. So if one wanted, for example, to determine the Greek letters used to write North Arabian names, then one can use the database to easily delimit the corpus by region or time and generate the results instantly.

Workflow and Publication

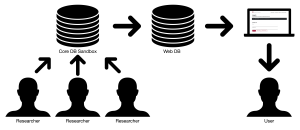

Once a project's core database is defined, researchers, such as international collaborators, postdocs, or graduate students are given access to that project's database. This team works directly in the backend, that is, they input data directly into the database using administrative GUIs and run prewritten scripts that shuffles the data throughout the database.

The DLATO Core Database is designed for the "next generation's" scholars. A minor knowledge of SQL, the computer language used to operate Postgres is required. The DLATO team trains project directors in the basic of SQL in order to work on their projects. Because relational databases are essentially interconnected spreadsheets, most team members can complete the initial textual input in spreadsheets.

The Structure of the DLATO Core Database

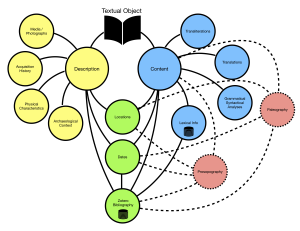

The core database is structured around textual objects and captures both descriptive data about the object as a artifact and the object's textual content.

The object's physical characteristics, archaeological, and curatorial information can be captured as well as links to media files. In computer speak, this is referred to as the object's metadata, and includes links to media files, such as photographs. Domains that overlap with textual content such as dates, locations, and scholarly bibliography capture data together so that complex searches of metadata and content can be easily written.

The more complex side of the database captures textual content. Due to the complexity of textual and linguistic data, many projects choose to separate metadata from textual content and use a markup language to input and "tag" features in textual content. This is a costly and complicated process that introduces a greater possibility of scholarly error than the structured database model used by DLATO. Furthermore, a great amount of processing power many be needed to run even simple queries in mark up languages, which means searching the text or tags may be slow. The DLATO Core Database captures all data within the database itself. This means the incredibly efficient Postgres software is able to process even the most complex queries almost instantly.

The DLATO Core Database is designed to facility the basic needs that any philological project would have. This includes the ability to input the text content in Unicode according to any scholar's reading (transliteration), provide translations, and input grammatical information on a word-by-word basis. The database also houses a project specific lexicon, which can be seen as a database itself and externally link to any other permalinked lexical project.

Scaleability and Feature Growth

The DLATO Core Database's structure is highly flexible and can be used to facilitate any line of inquiry a scholar may have. For the sake of efficiency and speed of input, the DLATO Core Database processes textual content on the word level. Using the power of Postgres, however, it is easy to expand the database so that a scholar may analyze textual content on a letter-by-letter/sign-by-sign, or even on the level of the stoke of each letter. For a test case, see James D. Moore's presentation at the University of Gronnigen. (https://youtu.be/ityZ55ZD5Cw?feature=shared)

Many projects concerned with historical content are interested in prosopography, and DLATO Core Database can be used for any type of network analysis, including prosopography. It is easy to organize data in a DLATO project so that relationships between persons (or any other nodes in a network) become apparent. The OCIANA project uses a legacy feature similar to this, but a DLATO project user can define any constraints by which they wish to compare nodes (e.g., objects, persons, concepts, actions) across a network. For an example of this in action see the DLATO Publication, Moore, Aspects of Judean Life, chapter 8 (Eisenbrauns, forthcoming).

Website Publication

Because the database is an SQL backend, projects can build websites, such as DEAPS, to present their data to the scholarly community and public. A DLATO projects can produce an API and website, much like DEAPS (deaps.osu.edu) relatively quickly. The DLATO Core Database was designed so that all research processing happens solely in the database and is not mediated or facilitated by a (costly) API.

This means that when it is time to publish a DLATO project, the a selective clone of the project's database is created, and its function is to simply allow users to perform predetermined queries, such as searching for strings of Unicode text, filtering objects on map, or the like. On, usually a weekly basis data is pushed from the research database, known as the sandbox, to the web database use a streamlined API written with Ruby on Rails. The OSU ASC Tech's Development facilities the building of the websites.